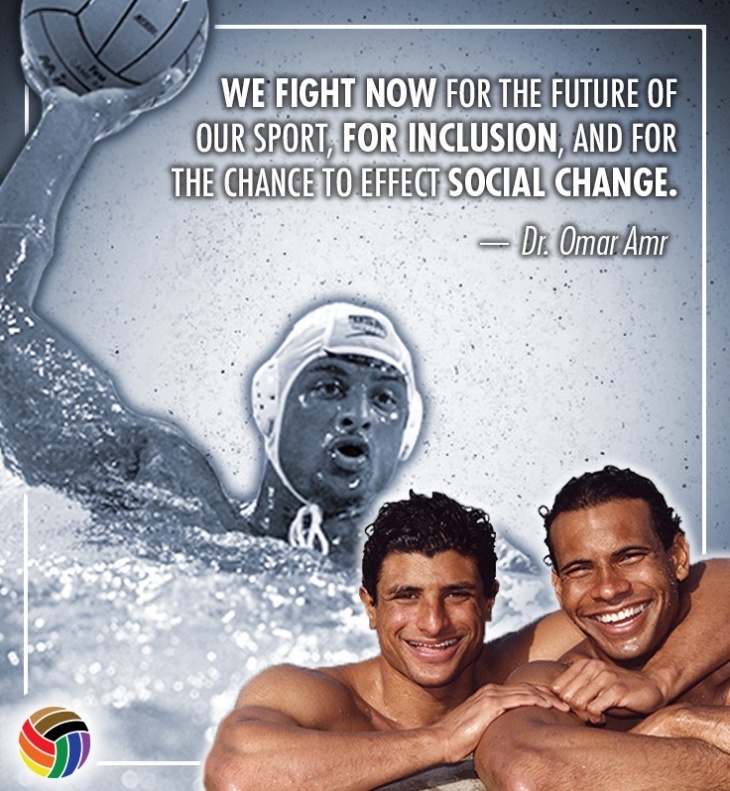

Olympian Dr. Omar Amr

How An ER Doctor Combated Racism In Pursuit Of An Olympic Dream

Over the next year, we're hoping to hear your stories about how race and ethnicity shape your life and, hopefully, publish as many of these stories as we can, so that we can all keep on talking. We're calling this effort Race in LA. Click here for more information and details on how to participate.

By Omar Amr, M.D.

"Just put your hands on the dashboard and calmly do whatever they ask you to do."

That was what my father taught me first when I was learning to drive, before he had even taught me to actually drive. At the time, I thought that was what everyone was taught — that it was normal.

A few years later, I was driving with one of my college friends. We saw the lights flashing behind us and pulled over to the side of the road. I immediately did what my father told me to do, but began to panic upon watching my friend casually exit our vehicle and start talking to the officer.

I thought the officer was either going to pull out his gun or throw him in handcuffs, but none of that happened...because my friend was white.

Following my friend's lead, I opened my door. Before I could even get my feet on the ground, the cop with his hand on his gun yelled to me, "Get back in the f***ing vehicle!"

It was then that I realized what I had been taught was not normal for everyone — at least not for white people.

WRONG SKIN, WRONG RELIGION

As the son of Egyptian immigrants, I'm technically African American, though I've never considered myself a part of the Black community. Yet, thanks to my curly hair and dark skin, I'm often mistaken for Black. Like the rules my father tried to instill in me during that driving lesson, I quickly learned that with Black skin comes a different kind of experience with society.

Though I didn't understand it at the time, my first memorable experience with racism in law enforcement happened when I was 12. A cop pointed his gun at my mother and me over a parking violation. My father came out of our apartment just in time to hear the officer call her a "bitch n*gger." My father immediately stood in front of us, blocking me from view, and instructed the officer to point the gun at him instead.

What my 12-year-old brain gleaned from that experience was, "My dad is a superhero and police officers are dangerous."

In theory, police officers are supposed to be our real-life superheroes, coming to save the day and help us when we need it. Unfortunately, members of the BIPOC community have been conditioned to fear law enforcement. They are supposed to "serve and protect" us, but how can they do that when they perceive our skin color as a threat?

I grew up in East L.A. in the 1980s. The differences in my complexion and religion made me the target of racial slurs on a daily basis and beatdowns by white kids for no reason than I was "other." Sadly, the poor treatment I received wasn't limited to my peers.

In elementary school, I had a teacher tell my parents I needed to be held back because I was a "bad student." Admittedly, I had trouble paying attention and was a little overactive, but for white students they called that ADHD, not "bad." Luckily, my mother insisted that I would be fine, and I was not held back.

My practice of Islam was also a problem for my teachers in grade school. My first grade sat me down and told me that being Muslim meant that I was going to hell and that I should convert. There were times that I was pulled out of class and forced to sit in a Bible studies truck which wasn't part of the school curriculum, but parked on our campus sometimes. Here, I was told being Muslim was "evil."

TROUBLE IN THE WATER

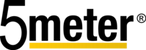

Growing up, I excelled in a predominantly white, notoriously non-inclusive sport: water polo. I was strong in the water, and fast. When it came time for college, I was recruited by Division I universities in both water polo and swimming.

I ended up at UC Irvine, playing for one of the winningest coaches in the history of water polo. A number of his players over the years had gone to the Olympics, and I had my sights set on becoming one of them.

Competing in a collegiate pool, I hoped things would be different than my formative years in school. Water polo is a tough, physically-aggressive sport, as fast-paced as basketball except in the water. I hoped my skin color and religion would matter less than my ability to score goals.

But at a tournament early in my college career, a player on an opposing team told my Black teammate he was going to "make his Black ass bleed Black blood."

At another tournament, an opponent called me a "n*gger" loudly enough for the coaches and officials to hear. Rather than penalizing the player who'd used the slur, the official took me out of the game so that, as he told my coach, I wouldn't retaliate. The other player was allowed to stay in the game.

Undeterred, I dedicated myself to both my sport and my academics. My grades were consistently at the top of my class, and I had my sights set on becoming a doctor. At the end of college, I was invited to join the U.S. National Water Polo Team.

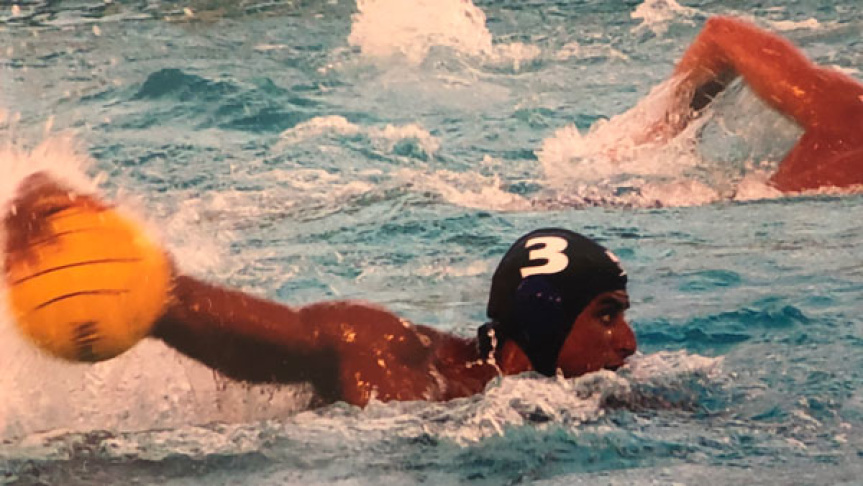

The decision was easy: delay medical school in order to vie for a chance to play in the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney, Australia. I had been admitted to Harvard Medical School but had convinced the dean to let me defer so I could focus on training. My lifelong dream of becoming an Olympian was so close I could almost taste it.